The Mandate is a newsletter on topics that men don’t like to talk about. It’s written by Olympic Medalist and frequent Men’s Health contributor Jason Rogers. If you enjoyed this content, please give it a heart. You can follow Jason on Twitter here. If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe below for free.

For as long as I can remember, I have been the kind of person who will leap at any opportunity to earn a prize or an award. I submit as evidence the fact that I spent nearly two decades competing in fencing, a sport that is the financial equivalent of knitting. If you get to the absolute top maybe you can make some cash. (I’ve seen some pretty badass Etsy pages with expensive-looking, reverse-stitched sweater vests). But in general, you must accept that fame and fortune are unlikely to be in the cards.

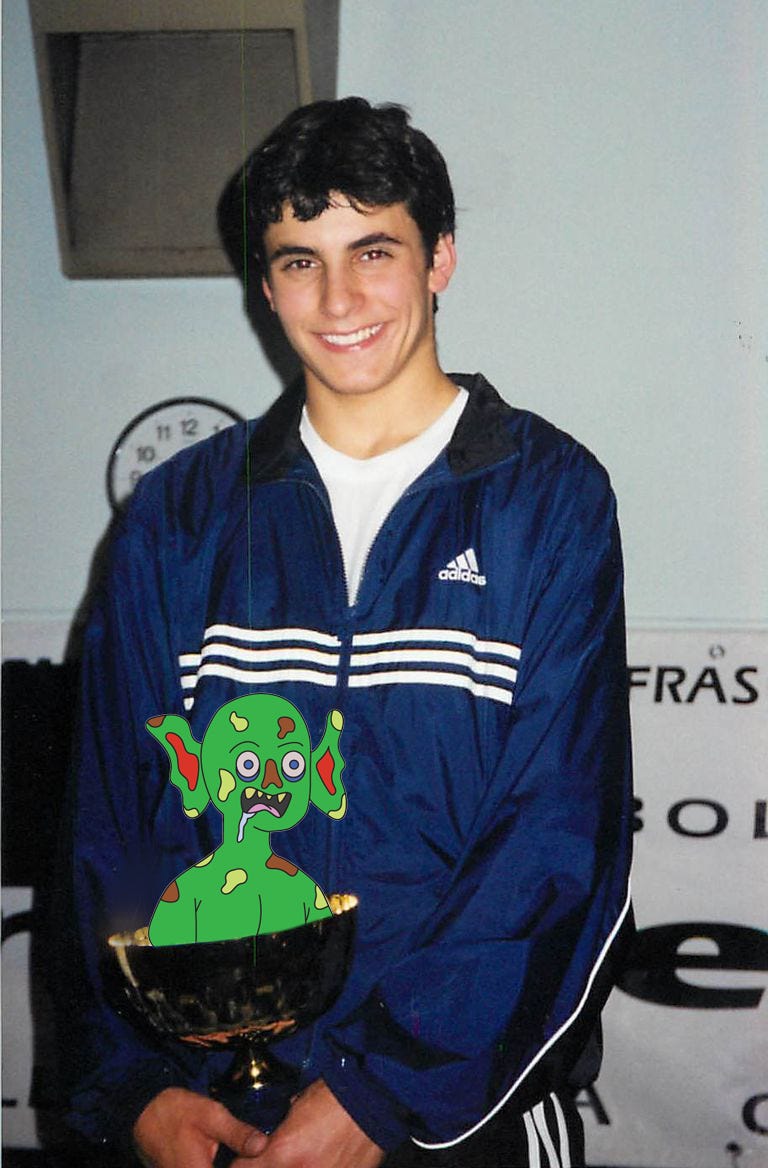

But, oh boy, do they give you lots of shiny things. Over the years, I have gotten rid of several large moving boxes full of trophies and medals. My athletic CV is a laundry list of titles that end with “champion,” the most glittering of words. I once received a replica sword after winning a tournament. If that’s not the adult version of a boy’s dream, I don’t know what is. The only better example I can think of might be becoming a professional race car driver and winning a life-sized version of a Hot Wheels bed. However, race car drivers actually make money. So, on second thought, that comparison does not work.

Of course, I am not unique in my love of accolades because the drive to be recognized for our efforts is universal. Deep down inside, we’ve all got a praise goblin, a ravenous creature that survives off of being told we are great. However, it would be an understatement to say that mine is a bit much. I have spent a huge portion of my life slaving to please this overgrown, greedy monster. However, each time I have nabbed a new (and often greater) achievement, it satiates him for an hour or so. Then, he starts getting angry and yells “I want more!”

As you would expect, my (mostly) unhealthy relationship with approval dates back to my childhood. My parents often say that I was the perfect baby — I rarely cried and held a certain hypnotizing effect over strangers. If this was some kind of parenting tactic, it was genius because I think spent the rest of my young life trying to live up to the angelic standards of my past. I worked really hard in school and earned praise-worthy report cards and academic gold stars. I was also very popular with my friends’ moms due to my extreme politeness. To this day, my friend Spencer likes to imitate the obsequious way that I would thank his mother for cooking us dinner. (“Thank you VERY much”).

However, when I started fencing, my interest in awards notched into a new gear. After winning my first national tournament, I quickly realized that I liked earning trophies. Or I should say, I really liked that other people seemed to like that I liked earning trophies. That feeling only amplified when, at 13, I became one of the youngest fencers to earn the top rating (an “A”!) by beating some of the field's best adults. Many people at my fencing club described that achievement as “incredible.” And, at that moment, my future life path presented itself to me like a yellow brick road rising from a vast expanse of empty dirt. It felt like I had cracked the code. My job was to earn medals and ribbons and good grades. If I could do all of those things, it meant that I was getting an “A” in life.

At this point, my story sounds like pretty much every over-achieving kid; however, things got more complicated as my college decision loomed on the horizon. By that point, I had secured my place among the upper echelons of junior fencing, attending and sometimes winning competitions around the world. However, even though I had earned the nickname “golden boy,” I also was painfully aware that I was not charting along the same developmental path as my peers. They seemed to be fueled by a kind of hormonal fervor, an electric jonzing in their bones that I simply did not feel.

That compounded when my initial forays into sexual experimentation did not go well. I mostly fumbled and withdrew from various new partners. Each experience sliced me like a papercut. The first few were tolerable, but over time, they formed a deeper wound that became difficult to ignore. This budding discomfort with myself as a sexual being eventually crystallized into an aspiration that would guide nearly all of my critical decisions: If I couldn’t be successful in the bedroom, I was going to make damn sure that I was crushing it everywhere else.

At that point, my fencing ambition kicked into overdrive. I had thought theoretically about the Olympics, but it soon became an obsession. I passed on going to Columbia University to attend the Ohio State University simply because I thought that the coach — a Russian three-time Olympic Gold Medalist — could help me achieve that dream. Charting that course eventually turned me into an award-winning machine. Academically, I became a teacher’s pet, earning a near 4.0 GPA and all kinds of regional plaudits like the “Big Ten Conference Medal of Honor.” (I don’t even remember what that was, but it was given out at a banquet with lots of people, so…HOORAY!). Athletically, I was the model workhorse, arriving before practice and staying late.

My new coach invested heavily in my development, so much so that he would call me randomly on the weekends so that I could come and take lessons from him in his backyard. I progressed rapidly as an athlete, but I also became subsumed by the impossible standards that I had set. Of course, I was thrilled to reach new competitive heights in fencing because those achievements served as symbols of my hard work. But when I look back, I realize that I was probably more motivated by the moments following a grueling practice when my coach would say, “good job, boy” in his barely comprehensible English. Receiving his affirmation was like a straight shot of dopamine. It reminded me that everything was going to be ok.

Well, my plan worked out while not working out at all. I did manage to arrive at my goal of winning an Olympic medal at my second Games in 2008 in Beijing. However, I quickly descended from that euphoric high to a lifetime psychological low. Even as I held the shiny object in my hand, I finally realized that no achievement could fill the void I’d created inside. The only way to restore any sense of well-being and happiness was to confront my bedroom anxieties head-on, which I eventually did. Things undoubtedly got better. But on some fundamental level, I was not able to adjust my relationship with praise. I still needed other people to clap for the things that I did to prevent myself from feeling lost.

After retiring from fencing, I started working in the advertising industry through a fellowship program that treated us like royalty. We had direct access to some of the best and brightest people in the company network, including many of the subsidiary agencies’ CEOs. They also flew us to France to do a week-long workshop in a literal chateau. I tell you that not brag, but rather to underscore that feeling invested in constantly fed my goblin and made me feel like I was doing something important — even though my job often amounted to figuring out how to sell more fabric softener and mayonnaise.

Still, I felt adrift in this new world because, truth be told, I missed my trophies. When I was fencing, it had all been so clear. If I did well, I received a physical monument and a numerical ranking as an emblem of my awesomeness. I had none of this clarity in my new office job. I would get attaboys here or there from my distressed, distracted bosses. (Fact check: that’s unfair, most of my bosses were actually incredibly generous with their time and interested in my creative and emotional development). I would also receive a performance review every year; however, in those meetings, my shortcomings were packaged inside a delicious compliment sandwich and articulated with such delicate abstraction that I wanted to grab my boss by the lapels and shout, “For the love of Christ, can you please just tell me if I am good at this or not!?”

In 2017, I left the advertising world to write. I thought this decision reflected a new, healthier relationship with my praise goblin because it was the first time I had ever committed myself to a craft that I did not explicitly have “permission” to do. In fencing, I had been anointed as some kind of young phenom. And the advertising fellowship had “chosen” me through an admissions process similar to the Ivy League. With writing, I had only assimilated a few stray compliments from colleagues (“you write good!”) and some fancy test scores (you are a certified fancy word knower!). I pursued it primarily because it felt right, and I thought I had an interesting and important story to tell.

However, I soon realized that I had run straight into a new kind of validation engine that was, perhaps, more insidious than the ones I had previously fled. I would need the approval of various gatekeepers, namely an agent and editors. More importantly, success in writing is roughly judged by popularity, sales, and critical acclaim. So, my previous need to please the imaginary group of people in my head who served as my ultimate judge and jury had now transformed into the task of cultivating a real group of readers who would like and share my work.

The first published piece of writing I completed was the story about struggling in the bedroom during my Olympic career. I have been asked why I decided to put that out into the world considering it’s such a taboo topic among men. There are still moments today when I look back and think that the version of myself that pitched and wrote that piece was a deranged lunatic. In the weeks before that piece came out, I was literally vibrating with fear as I considered what others might think. Thankfully, my wife (who actually encouraged me to write about the topic in the first place) was my rock and helped keep me focused on the why: If I had read an article like this when I was 15 and was going through the same thing, it would have made me feel less alone.

However, it’s so much more complicated than that. I would be remiss if I didn’t also acknowledge that, alongside the terror I felt, there was a twinkle of confidence that this act would be acknowledged with a certain kind of awe and respect. After the story was online, many people reached out to me in private messages to commend me for my “bravery.” The vainest parts of myself want to portray my reception of those compliments as valiant and stoic. However, deep down, I know that my praise goblin was gorging himself on a feast of delight. And, per usual, no matter how much he had been fed, it didn’t take him long to start looking for his next fix.

From there, my work expanded to interrogate modern masculinity, which is another way of asking the question: how do guys become better men? Let’s say we met each other at a cocktail party, and you asked me why I am interested in that topic. I would undoubtedly have a bevy of (entirely true) answers for you. I genuinely believe that many men (myself included) have a bunch of garbage ideas about how they are supposed to navigate the world. I want to bring awareness to those ideas so that we can construct better ones, together. However, what I probably would not say is that I am also drawn to it because it is likely to generate a lot of praise.

Also, as a cis, white, hetero man — that is also the product of private schooling and an elite sport — I’m still working out how to think about my place in the world. Men that look, talk, and act like me have taken up a lot of space over the years. And we have arrived at an important moment when guys should be thoughtful about when to offer their opinions and when to take a step back. Even the seemingly commendable act of publically interrogating one’s privilege may be counterproductive because it shouts for more attention rather than less. Worse, assuming the role of the critiquer (of masculinity, for example) can also serve as a strategy to avoid becoming the critiqued. “Look I get it,” a man says, “I’m one of the good guys!” Most days, I am confident that’s not my motivation, but sometimes I do wonder if that man is me.

The way that I am trying to unravel my confusion about this issue is to go straight into the ball of yarn. I am dead set against becoming one of those annoying, virtue-signaling social media bobbleheads that does everything for likes, followers, and subs. And yet, I cannot ignore that my desire for praise sometimes pushes me towards certain behaviors — like excessive earnestness — that is clamoring for said likes, followers, and subs. The unconscious mind will always tact towards a schtick that is working because, as long as the human species has trafficked in recognition, people have reshaped themselves for broader appeal.

But it’s clearly gotten worse in the digital age because our phones have turned every moment into a potential tap dance. If you choose to use those tools to share your life and thoughts online, there comes a terrifying moment when you realize that you can’t always tell when you are behaving authentically and when you are performing for spectators. Even (or perhaps especially) when that spectator is yourself.

How Was This Edition of The Mandate?

Please tell a friend about us and hit the heart button; it helps other people discover the content!

While I risk the hazard of delighting your praise-goblin, this article was genuine and interesting enough to get me to comment, so "you write good". :D

This is just your ego always wanting more! The remedy is being grateful, for what you have!