About a week ago, my wife and I packed up and stored all of our earthly belongings in preparation for a temporary reprieve from LA. With the city in a weird state of pandemic purgatory (part open, part closed), we thought, why not ship off for a few months to a place with more wide-open space? Hello Hawaii!

We picked Oahu (in part) to satiate my eternal appetite for surf. The North Shore of the island is widely regarded as the premier place for wondrous waves. To be clear, I have no illusions that I’ll be launching into 12-foot monsters at Pipeline (the most famous of them all). But the storm activity in the North Pacific during the late fall and winter should offer a constant buffet of little screamers better suited for my intermediate skills.

Despite growing up around surf culture in Southern California, I came to the sport quite late in life. There were short periods where, as a young teen, I’d paddle out with friends. But I was far too obsessed with skateboarding and, later, snowboarding to give it a proper go. Then, as I neared the end of high school, fencing took over my life. My coach didn’t respond well to me kickflipping my way to a groin injury before a major international competition. So, doing anything but train for tournaments soon was out of the question. Goodbye skateboarding, snowboarding, and (the prospect) of surfing.

Fast-forward to three years ago, nearly a decade after I retired from fencing. I was living in London with my wife (then fiancée) and working in the advertising industry. However, all the years that I’d lived away from Los Angeles had left me longing for the sun and sea. So we decided to cross the pond and settle into a little apartment about a half-mile from the ocean in a neighborhood called Venice.

I’d spent so long missing the California beaches that when we arrived, it was pretty much the only place I wanted to be. Then, it was a pretty logical step to grab a board and paddle out here and there. Those initial splash sessions took me back into a mindset that’s hard to find in adulthood — the kind of pure presence that makes you feel open and free. And the rest, as they say, was history.

It wasn’t all fun, though. Learning (or re-learning, in my case) was an exercise in masochism because the ocean can be a terrifying place for a beginner. It helped that an old friend (🤙 Evan Powell) gave me a board and helped bring me up to speed. Still, in the early months, I spent more time under the wave than on it.

However, I found that a bad beating or horrible hold-down paled in comparison to the machismo I encountered in the lineup (the main area where surfers catch waves). Forget the gnarly sets; the gnarly locals were far worse. Oddly enough, the behaviors I observed were at once novel and familiar — the kind posturing that, as a former pro athlete, I’d encountered a thousand times before. I certainly can’t claim to be an expert in surf culture, but I thought I would offer some of my observations of this strange, new world.

Bro’s Only Surf Club

Although Hawaiian Queen Kaʻahumanu once dominated Waikiki's waves, women have long struggled to find a foothold in this sport. The statistics suggest that they represent somewhere between twenty and thirty percent of surfers. But I couldn’t tell you the number of times that I’ve paddled out into the near-exclusive company of men.

That’s definitely NOT because they don’t surf well. In fact, one of the surfers I most enjoy watching is the reigning women’s world champion, Carissa Moore. The film below does a better job rhapsodizing about her than I will. But suffice it to say that she’s a veritable virtuoso — blending speed, power, and finesse in a manner rarely seen among those with a Y-chromosome.

Sadly, many female pros like Moore have had to fight their way to success because territorial guys have tried to put them off of the sport. On these inhospitable conditions, former 7-time world champion, Layne Beachley, wrote the following in a Guardian piece in 2017:

I felt alone, one of one, the lone female figure playing in a male-dominated environment that lacked the support, encouragement and acceptance we all need to survive and thrive. I was teased, cut off, told to get out of the water because I was a girl, advised that girls don’t surf, and to go mind the towel on the beach.

Things have definitely changed since Beachley’s early days. But, as the editor of Surfer Magazine, Ashtyn Douglas, recently pointed out, certain cultural behaviors remain that suggest female pro surfers continue to be an afterthought:

In surfing, we’ve historically judged the aquatic talents of a woman in terms of how they measure up to a man’s. Tyler Wright, Carissa Moore and Steph Gilmore are often praised for surfing “as well” as the guys on Tour. Big-wave chargers like Paige Alms and Bianca Valenti get props for sitting at the peak and “hanging with the guys” at Jaws and Mavericks. Santoro’s “got balls,” for stroking into one of the heaviest waves of the day.

It’s two-foot out there

The ocean produces some unbelievable monsters. However, because a wave is not a stationary structure, rather a moving organism, it isn’t easy to precisely measure the size of a wave. I’ll spare you the complexities, but suffice it to say that that most common is method is to measure from peak (top) to trough (bottom), with most forecasting services using human comparison for context (e.g., chest-high, head-high, double overhead, etc.).

Some Hawaiians reject that method, preferring their own, which usually cuts the estimate by approximately half. So, if you think you’re headed out into twelve-foot surf at Sunset Beach (which is serious, even for a decent surfer), a local might tell you it’s six-foot at best. There are many theories as to why this disagreement exists. The most common I’ve heard is that Hawaiians prefer to measure from the back of the wave (which is probably untrue). Whatever the explanation, it translates to a system that downplays risk. And many surfers under-call their waves (say they were smaller) to demonstrate bravery over fear.

After I arrived in Oahu, my friend Andrea sent me a joking text to see where I stand. “How’s it going over there,” he said, “Are you already calling everything a one-footer?” I can tell you the answer is a resounding no. Because, unlike those that grew up on a rock in the center of the ocean’s fury, I most certainly am not comfortable playing it cool.

You won’t go

However, measurement means nothing when you’re out in the elements, as big wave surfing pioneer, Buzzy Trent, indicated when he famously said, “Big wave surfing isn't measured in feet but in increments of fear.” As a result, a kind of reverence exists for those who push the sport to its edge. And rightly so. Watching Maya Gabeira surf a 73-footer* and set the record for the largest wave ever surfed by a woman (which I will note was larger than the winner of the men’s award that year) fundamentally changes what we think is possible. And that’s great, in my view.

However, it becomes a bit murkier when you step back and look at a competitive culture that produces such feats. In the recent HBO documentary, Momentum Generation, which details the formative years of a group of surf stars, 11-time world champion, Kelly Slater, tells a story from his teen years that I think does a good job of making this point. He and pro-surfer-turned-musician, Jack Johnson, were out in the lineup on a big day. And, as a set (a series of large waves that come in a row) rolled through, Slater allegedly said to Johnson, “You won’t go.”

Johnson responds by catching the wave. However, when he bails near the end, the reef and his face collide, leaving him with 150-stitches and some banged up teeth. You can justifiably argue that this is just playful teenage stuff. Also, these guys are both in their forties now, and that the anecdote in no way represents who they are today. But the story illustrates how surfers can act tribally, pushing each other to take bigger and bigger risks. You earn status within the group when you “go,” leaving an alternative that’s anathema to most teens: being viewed as less manly because of your fear.

And while stories like this are a dime a dozen in extreme sports, the verbiage used by Slater likely arises directly from one of the most inspiring figures in surfing lore. Eddie Aikau was a legendary Hawaiian during the 70s that earned his reputation as both a fearless surfer and a courageous lifeguard by rescuing hundreds at the treacherous big wave spot, Waimea Bay. When the waves get super-sized on the North Shore, Oahu hosts an annual tournament in his name in which surfers push themselves to the limits. And, although Aikau died under tragic circumstances, his legacy lives on in the Hawaiian adage, “Eddie Would Go.”

That’s my wave

However, that’s not the only way that group dynamics play a role in such an individual sport. Waves come in limited quantities, and “locals” (the tribe of surfers that consider a wave their home territory) aren’t always willing to share. Nearly all Hollywood surf films (e.g., Blue Crush or Point Break) include a perfunctory scene to showcase this aspect of surf culture. And as cringeworthy as they are, the moments depicted aren’t that far off from the occasional extremes that locals will go to defend their turf.

At many surf breaks, you’ll hear guys (mid-argument) scream, “I’ve been surfing here for twenty years, and I’ve never seen you before.” Being a local is the ultimate trump card because it means you are part of the in-group (by virtue of how close you live to the spot or how often you surf there) and thus entitled to the better waves.

If someone drops in on a local (i.e., violates surf etiquette by taking off in front of a surfer who’s in priority position for the wave), others will quickly come to his defense. And I’ve watched at least a half dozen non-locals get bullied out of the water** (I literally saw this happen a few days ago).

Sometimes, a verbal clash can even turn physical. While it’s more than a decade old, the NY Times did an op-doc on the history of violence amongst groups of Hawaiian local surfers. I should point out that the islands are, in no way, unique in this respect because it’s well documented that surfers allow bravado to get the best of them all around the world.

Don’t be a kook

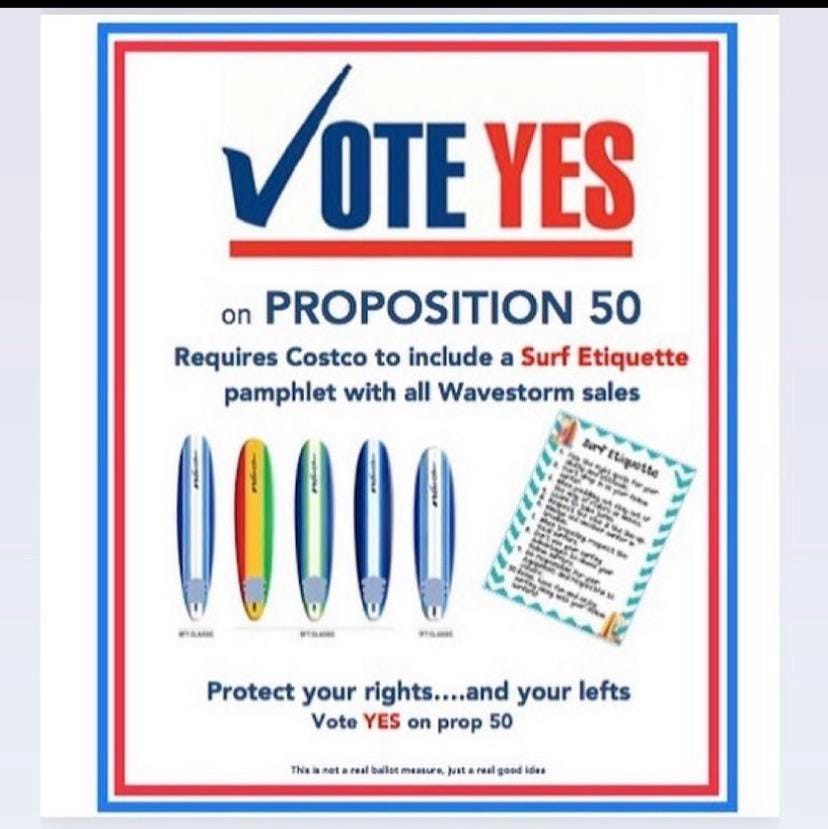

Most of the time, squabbles break out for no good reason. But a stern warning is occasionally necessary when a surfer has a low ocean IQ. Not everyone that buys a foamboard at Costco does their due diligence. And, even those who make an effort to learn surf etiquette find that putting it into practice in the water is a difficult thing to do.

That’s because some of the rules, like waiting your turn, can be difficult to judge on a crowded day. And, often, disagreements are a matter of opinion. Others, however, are less so. For example, a surfer should never “ditch their board” (i.e., let go of it while trying to get over or under an incoming wave) because it can injure another surfer nearby.

This kind of infraction can get you labeled as a “kook,” the surf slang word for a beginner. And the term is hurled as a pejorative at newbies and experienced surfers alike. It’s also widely used on the internet, most famously on the popular Instagram account, Kook of the Day, which has evolved from a showcase of wannabe surfers to a home for various inside jokes and viral videos of unfortunate aquatic events.

But the humor invoked by Kook of the Day and surf culture at large is more nuanced than watching beginner buffoonery. The term is sometimes used to invoke self-referential irony because experienced surfers love imitating hapless newbies. And they are equally quick to sneer at someone they perceive to a poser and tell them that they “rip.”

At its core, the merciless mocking of kooks demonstrates a kind of behavior often seen within hyper-masculine groups best described by Dylan Hayden of The Intertia, a popular online surf publication:

Calling someone a kook in an effort to put them down, though, whether it’s to their face or among friends, is what Michel Foucault [a French Historian] would likely call an act of othering. That is, pointing out someone as an “other” to distance themselves and the group they belong to from that person. It’s artificial and super demeaning.

It may not be as socially unpalatable, but it’s akin to other words (e.g., “pussy,” “fag,” etc.) used by boys and men to separate another from his status. It says you don’t belong here. You must earn our respect (e.g., through superior skill, daredevilism, or other status-worth tactics). Otherwise, you can’t be a part of this group.

Waves of Change

I would be remiss if I didn’t underscore that surfing is not unique in many of these respects. And many of these behaviors are endemic to male sports. Plus, most surfers aren’t like this (at least not in my experience). And I’ve chosen examples that are far more extreme than the benign interactions that happen every day.

Not to mention the fact that the sport is entering a time of flux. The World Surfing League, which hosts the premier pro tour, announced in 2018 that it would become the first US-based global sports league to prize money equality. And although there is a small loophole behind the PR headline (they don’t have to have the same number of events), female surfers and the media were quick to celebrate the change.

While the sport has many highly visible male surfers that are, shall we say, more inclined toward unhelpful antics, it also offers plenty of alternative role models. David Rastovich, the Kiwi-born, Australia-based freesurfer (a pro that travels the world appearing in surf films rather than competing), generally avoids the spotlight.

But when he does speak out, he focused on topics that are decidedly un-bro. In addition to serving as a surf activist focused on ocean conservation and ecology, his overall vibe suggests that, for him, riding waves is less a sport and more a moving meditation — a lifestyle that eschews conflict in favor of a connection with the natural world.

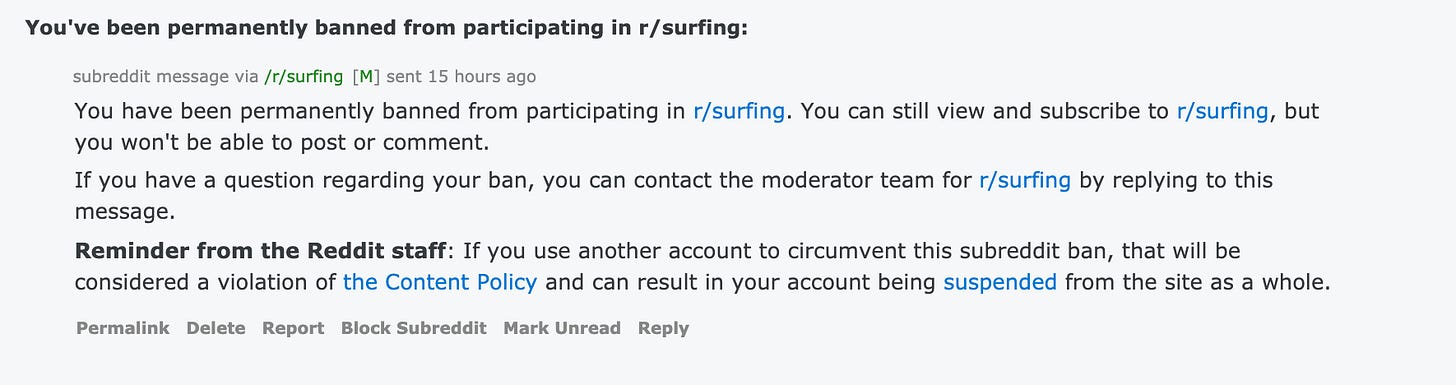

So all of that’s to say that, I choose to believe that surfing’s future looks bright, at least on the masculinity front. Then again, when I proposed to a popular Reddit surfing forum that the sport might have a bit of a bro-problem, I didn’t exactly get a constructive response.

“Stay in your lane,” one user wrote. “Write about scooters and pick-up lines.” (Maybe he’s confusing me with Alfie 🤷🏻♂️). Another insinuated that I was imposing a false narrative on a culture I didn’t understand. After that, the moderators removed the one helpful suggestion I received, then promptly banned me from the group.

Footnotes:

*Gabeira’s wave was actually the subject of major controversy in the surfing world. The runner up, Justine DuPont, very publically criticized both the wave measurement technique (she thought hers was bigger) and argued that Gabeira’s ride shouldn’t count because she didn’t “make her wave” (successful ride it all the way through).

**I should note that, occasionally, stern discussions are necessary. Some people surf a new spot so aggressively that it’s disrespectful and, sometimes, dangerous to others in the water.

How was this article?

Amazing | Good | Meh | Bad | Just show me a cat meme

About the Mandate Letter

I use this newsletter as a journal to work through my ideas and collect examples of broader trends that reflect how masculinity is evolving in culture. I would very much appreciate your input. If you come across interesting examples of this trend or others, please email me tips at Jason [@] jasonrogers.co. If you're reading this in your inbox, just hit reply, and your response will go directly to me. Also, keep up with me on Twitter & Instagram or text me at 310-299-9363.